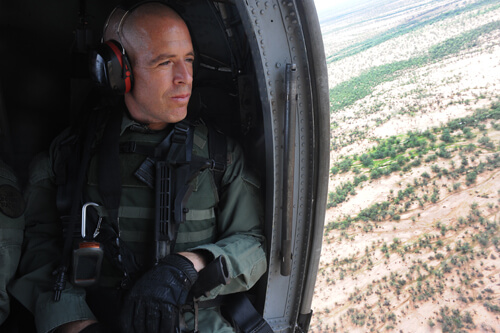

With his eyes on the horizon, Army 1st Lt. Eric Escobedo, a pilot with the Arizona Army National Guard’s B Company, 2nd Battalion, 285th Aviation Regiment, pilots a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter in an area along the Arizona-Mexico border as part of Operation Guardian Support, which provides National Guard assistance to U.S. Border Patrol and U.S. Customs and Border Protection along the Southwest border. For Escobedo, and other members of his unit, that support includes transporting Border Patrol agents to remote locations in the field as well as providing overhead security and surveillance.

With his eyes on the horizon, Army 1st Lt. Eric Escobedo, a pilot with the Arizona Army National Guard’s B Company, 2nd Battalion, 285th Aviation Regiment, pilots a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter in an area along the Arizona-Mexico border as part of Operation Guardian Support, which provides National Guard assistance to U.S. Border Patrol and U.S. Customs and Border Protection along the Southwest border. For Escobedo, and other members of his unit, that support includes transporting Border Patrol agents to remote locations in the field as well as providing overhead security and surveillance.

Army 1st. Lt. Eric Escobedo squints into the midday sun while performing pre-flight inspections on a UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter. Sweat beads and runs down his forehead as he rotates the tail rotor, having already checked various engine components and other mechanical elements.

While on the ground at a small airfield south of Tucson, Ariz., Escobedo, right, reviews weather data with Chief Warrant Officer 2 Leo Tocchini, left, a fellow pilot, and acting Supervisory Border Patrol Agent William Colson. Flying OGS missions in Arizona often means staging near the border, making it easier to respond to calls from the field.

While on the ground at a small airfield south of Tucson, Ariz., Escobedo, right, reviews weather data with Chief Warrant Officer 2 Leo Tocchini, left, a fellow pilot, and acting Supervisory Border Patrol Agent William Colson. Flying OGS missions in Arizona often means staging near the border, making it easier to respond to calls from the field.

The day is hot. Overwhelmingly hot. The kind of dry, baking heat that makes some use swear words to describe the punishingly unforgiving way it radiates.

As a helicopter pilot with the Arizona Army National Guard’s B Company, 2nd Battalion, 285th Aviation Regiment, the heat is nothing new for Escobedo. It’s a presence in many parts of Arizona, but especially so on the open asphalt of the flight line at Papago Military Reservation in Phoenix while preparing for a mission.

For Border Patrol agents, the focus is on curtailing illegal border crossings while stemming human and drug trafficking operations. Nero, the dog, assists with that and happily accompanies Border Patrol Agent Robert Husted, a dog handler and team leader with Border Patrol, on the Black Hawk.

For Border Patrol agents, the focus is on curtailing illegal border crossings while stemming human and drug trafficking operations. Nero, the dog, assists with that and happily accompanies Border Patrol Agent Robert Husted, a dog handler and team leader with Border Patrol, on the Black Hawk.

That mission today has Escobedo and his aircrew flying along the Southwest border as part of Operation Guardian Support, which provides National Guard assistance to U.S. Border Patrol and U.S. Customs and Border Protection.

“What we do here, for the UH-60 portion of it, is we act as [Border Patrol’s] transport to get them on-station in a timely manner,” said Escobedo.

The mission begins with a pre-flight briefing before prepping the aircraft for flight. Equipment and gear is loaded on board and distant-sounding voices crackle in the internal communication headsets as Escobedo and his fellow pilot, Chief Warrant Officer 2 Leo Tocchini, run through start-up checklists.

The aircraft comes to life as the whining hiss of the turbine engines fill the air. The rotors start to spin, languidly at first before getting up to full tornado-like rotation. After taxiing, the aircraft lifts gently off the flight line, held in a low hover before being pointed south, toward the border.

Kicked up by the rotor blades of the UH-60 hovering overhead, a whirlwind of dust swirls around an individual alleged to have crossed the border illegally. Part of a larger group, most were quickly detained by Border Patrol, though a few continued to push through the desert. Hovering above the individual, and moving with him, marked his location for agents on the ground.

Kicked up by the rotor blades of the UH-60 hovering overhead, a whirlwind of dust swirls around an individual alleged to have crossed the border illegally. Part of a larger group, most were quickly detained by Border Patrol, though a few continued to push through the desert. Hovering above the individual, and moving with him, marked his location for agents on the ground.

“Essentially, we stage at an airport nearby the border,” said Escobedo, adding that from there, they link up with the Border Patrol agents flying with them and go over any pertinent details for the day’s mission.

After that, it’s a waiting game.

“We wait for requests for air support from the [agents] out in the field,” said Escobedo. “When they call that request in, we get called out and everybody loads up on the aircraft. They give us their GPS coordinates and we go out to that area to help support them.”

For the Border Patrol agents, that means greater mobility and flexibility.

“The other day we were able to apprehend three different groups [who illegally crossed the border] within a two-hour window,” said acting Supervisory Border Patrol Agent William Colson, an agent with the Flight Tasked Mobile Response Team in Border Patrol’s Tucson Sector. “Traditionally, if we were just on the ground, that could take one agent four to five hours to apprehend one group.”

There are other benefits as well. Aircrews, and the Border Patrol agents they fly, can quickly investigate a sensor going off or something seen in a surveillance camera.

“If they get a ground sensor hit or some kind of ping off a camera, we go out there and try to figure out if there is actually somebody there,” said Escobedo. “It might be an animal that set off the trigger and it relieves the time it takes agents to get out there on the ground for something that could end up being nothing.”

After landing in a remote location near the Arizona - Mexico border, a Border Patrol team exits the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter piloted by Escobedo. Called in to assist agents on the ground with a group alleged to have crossed the border illegally, landings like this help prepare Escobedo and other pilots for overseas deployments where landing zones may be in rough conditions and not always identified in advance.

After landing in a remote location near the Arizona - Mexico border, a Border Patrol team exits the UH-60 Black Hawk helicopter piloted by Escobedo. Called in to assist agents on the ground with a group alleged to have crossed the border illegally, landings like this help prepare Escobedo and other pilots for overseas deployments where landing zones may be in rough conditions and not always identified in advance.

For now though, after linking up with Border Patrol agents at a small airfield south of Tucson, the wait is on.

“Sometimes we get a call right away and then it’s back-to-back calls,” said Escobedo. “Other times we sit awhile before getting a call.”

During the downtime, Escobedo and Tocchini work out refueling options while studying weather radar and maps, planning flight times and routes around possible severe thunderstorms. The heat cooks the cracked asphalt of the tiny airport, the occasional meandering breeze only hinting of cooler temperatures, rather than offering any real relief.

Border Patrol agents situate their gear on the Black Hawk. Some open snacks, others share stories of past calls or argue the merits of various sports teams. Soon enough, Colson strides briskly, purposefully toward the aircraft from the Border Patrol command vehicle on the side of the airstrip.

The helicopter rotor blades remain spinning as aircrew members and Border Patrol agents alike keep an eye out for a returning Border Patrol team after dropping them off to assist other agents in the field.

The helicopter rotor blades remain spinning as aircrew members and Border Patrol agents alike keep an eye out for a returning Border Patrol team after dropping them off to assist other agents in the field.

“We’ve got a call,” he says, while double-checking notes. “Let’s get going.”

Coordinates were passed on as aircrew and agents climbed aboard the aircraft. The engine was spun up and in short order the crew had the helicopter in the air, heading out over the sagebrush and dust, rocky hills silhouetted in the distance.

A group who crossed the border illegally had been detected and responding agents on the ground requested assistance. Equipment is re-checked in-flight and minutes later, after rounding a sloping hill, Border Patrol vehicles – bright white with an angled green stripe along the side – are seen contrasted against the red-brown terrain, parked on gritty trails offering only suggestions of an actual road.

Escobedo piloted the aircraft in a wide, loping circle around the agents on the ground. The group who illegally crossed were not far off, hidden among the low, scraggly trees and brush.

After a few circles, Escobedo landed on a bare spot free of underbrush, kicking up a whirlwind of gritty dust as the Black Hawk settled to the ground. A Border Patrol team quickly exited the aircraft, heading in to detain the group.

For the Border Patrol agents, the focus is on curtailing illegal border crossings, while interdicting human and drug trafficking operations.

Keen eyes keep watch for an individual who called 911 for assistance in the desert. According to a subsequent Border Patrol report on the incident, the individual had crossed the border illegally and after four days of walking through the desert with little water, he called for help with a cell phone. Incidents like that aren’t uncommon, said Escobedo, and can sometimes come from misinformation given to those who cross the border indicating that large cities are a few miles away.

Keen eyes keep watch for an individual who called 911 for assistance in the desert. According to a subsequent Border Patrol report on the incident, the individual had crossed the border illegally and after four days of walking through the desert with little water, he called for help with a cell phone. Incidents like that aren’t uncommon, said Escobedo, and can sometimes come from misinformation given to those who cross the border indicating that large cities are a few miles away.

“The integration definitely helps a lot with giving Border Patrol that ability,” said Escobedo.

But for Escobedo, and the rest of the aircrew, assisting Border Patrol helps with readiness for overseas deployments. During normal training exercises, landing zones are often pre-determined and cleared out, he said.

“Being out here, there are no [pre-determined] landing zones,” said Escobedo. “It’s just ‘here’s the GPS coordinate, land as safely as possible in the nearest location to drop off your guys.’ Being able to do that helps us when we deploy and have infantry guys in the back who need to get to the location as fast as possible.”

And then there’s contending with environmental factors – like dust, the heat and quickly changing weather patterns.

“As a pilot, it definitely has broadened my horizons for what I’m able to fly in,“ said Escobedo.

After dropping off the Border Patrol team, it was back in the air, flying overwatch. Most of the group was quickly apprehended, though a few individuals pushed on through the desert trying to evade agents. The Black Hawk hovered above them, the pilots moving the aircraft in time with the group to mark the position. Agents on the aircraft relayed the movements to agents on the ground until all were detained.

As Border Patrol wrapped up the apprehensions, another call came in – a 911 caller needing assistance in the desert. The individual had crossed the border illegally, according to a subsequent Border Patrol report on the incident, and after four days of walking through the desert heat with little water, he called for help with a cell phone.

Border Patrol agents sit quietly in the back of the UH-60 while being flown out on a call to assist agents in the field.

Border Patrol agents sit quietly in the back of the UH-60 while being flown out on a call to assist agents in the field.

“We see that sometimes,” said Escobedo, referring to the 911 call. For many in that situation, it’s a matter of life or death. That’s often a result of underestimating the distance and heat, which can sometimes come as misinformation from those who have led them to the border.

“It’s hot and some groups will head across the border into the desert after being told Phoenix or Tucson is a couple of miles away,” said Escodebo.

Minutes later, the Black Hawk hovered above the individual’s last known location, pinpointed using cell phone towers. Circling above a rocky outcrop, the individual was eventually spotted laying on a large rock. Seeing no movement, some aircrew members feared the worst, they said afterward, until he moved an arm.

With last light of day filtering through the sky, aircrew members conduct a post-flight inspection on the Black Hawk. Because of the high operational tempo, one of the biggest challenges is ensuring the aircraft is mission ready at all times, said Escobedo. In addition to the OGS missions, the aircraft are also used for a variety of other missions and training requirements.

With last light of day filtering through the sky, aircrew members conduct a post-flight inspection on the Black Hawk. Because of the high operational tempo, one of the biggest challenges is ensuring the aircraft is mission ready at all times, said Escobedo. In addition to the OGS missions, the aircraft are also used for a variety of other missions and training requirements.

With the Black Hawk hovering overhead marking the location, Border Patrol agents on the ground navigated the rocky terrain by foot until they reached the individual. Bottles of water were dropped from the helicopter, requested by the ground agents, who then detained the individual.

No further assistance was needed – the individual was dehydrated, but otherwise healthy, said agents – and the next order of business was to pick up the agents dropped off in response to the earlier call.

For Escobedo, working with Border Patrol has been seamless.

“We already had that relationship built through Counterdrug [operations],” he said. “Since OGS has kicked off, that relationship has flourished and it’s just gotten better.”

Colson agreed, adding that his team is part of a dedicated air operations element.

“All we do is provide air interdiction agents and air observers [to work with] other agencies and that has provided for an easy transition working with the National Guard,” he said.

But there are still challenges.

“The biggest challenge is trying to get the aircraft ready to go because there’s a high demand,” said Escobedo, adding that the maintenance crews are key to keeping the aircraft flight-ready. “On top of working with Border Patrol, we still have our own missions we have to do.”

Though, that’s fine for Escobedo.

“I joined the National Guard so I can help the state that I live in,” he said. “Being able to do that by securing the border and helping Border Patrol, it’s been extremely rewarding for me.”