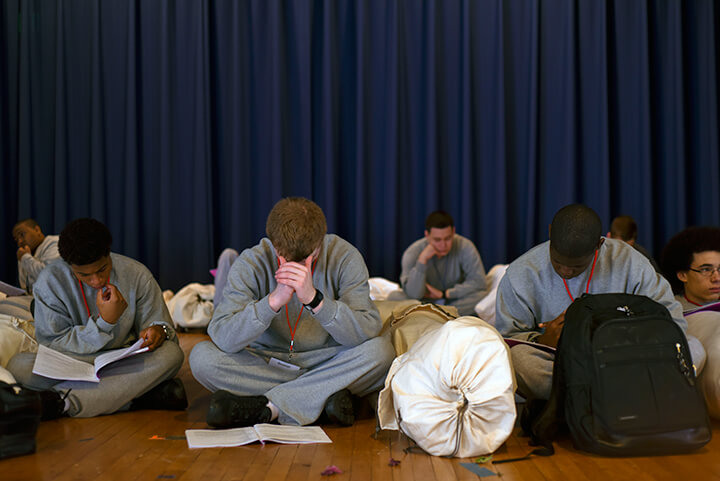

Candidates at the academy bury their heads in their student handbooks as they wait for additional instructions from cadre members. Downtime often means continued studying for candidates at the academy, even before they're officially accessioned into the program.

Candidates at the academy bury their heads in their student handbooks as they wait for additional instructions from cadre members. Downtime often means continued studying for candidates at the academy, even before they're officially accessioned into the program.On a crisp winter morning, a slow trickle of teens in gray sweat suits began to line up outside a large, red brick building. They carried pillows under their arms and duffle bags over their shoulders. Some talked softly with parents and other family members; others stared blankly at one another, or at nothing at all. As the minutes ticked by, the building's closed doors only prolonged the suspense and uncertainty of what was to come.

None of them knew what to expect once those doors opened and they stepped inside for in-processing at the Maryland National Guard's Freestate ChalleNGe Academy. They also didn't know they would find themselves facing 1st Sgt. Job Stringfellow — an imposing, energetic, wide-shouldered man in a crisp, tan military-style uniform and black drill sergeant hat — who would greet each teen with a question: "Are you ready to come through my door?"

Stringfellow, who is responsible for the day-to-day structure at the academy, had other questions too.

"Where you from," he asked each teen who stood before him. Some stammered, others defiantly replied, but no matter the answer, his response stayed the same.

"That's where all the quitters come from," he said. "You come to me to quit?"

His questions and deliberate replies emphasized two things: This is a different world the teens were about to enter and that while there, he wasn't going to let them give up — even if they tried.

Joshua Griffin and other candidates lay out their belongings during an inspection to ensure candidates have all required items. Cadre members call out items and candidates respond by holding the items up high, confirming they have them before putting them in their duffel bags.

Joshua Griffin and other candidates lay out their belongings during an inspection to ensure candidates have all required items. Cadre members call out items and candidates respond by holding the items up high, confirming they have them before putting them in their duffel bags.Stringfellow's imposing demeanor may have caused some to question their decision to enroll in the academy, part of the National Guard Bureau's larger Youth ChalleNGe program, an education and self-discipline program for "at-risk" youth conducted in a military-style environment.

Other teens, may not question the decision until tomorrow morning when they wake up at 5 a.m. to begin their daily routine, said Charles Rose, program director at the academy.

"It's often a big change from what they're used to," he said.

Each day will be structured similarly, beginning with early morning physical training. During their time at the academy they will attend GED preparation classes, create budgets, set future goals, participate in community service projects, sharpen their marching skills and work together to clean the facilities all with the expectation to do what they are told when they are told.

Once they complete the five-and-a-half month residential phase, the teens will spend another 12 months working with a mentor and academy staff to fulfill goals they set during the residential phase.

On that first morning though, the candidates — who won't become full-fledged cadets for another two weeks — were given a flurry of directions from in-processing staff. Go here. Go there. Sit down. Stand up. No talking. Dump your bag. Pack your bag. Do it again. There were no smiles or laughter as they completed in-processing procedures, many thinking of the months ahead and the tremendous emotions of saying goodbye to family members.

For Ronny Colindres, a candidate at the academy, those emotions became somewhat overwhelming, he said, adding he felt the academy represented his last opportunity to change his life.

"It's a lot of pressure because if you get put out then that's it, there's nowhere else to go," Ronny said. "You're done. I'm done forever."

Ronny, 18, said he was dropped from public school for repeating the ninth grade too many times and hopes that Freestate will not only provide him with the education he needs to be successful, but will also give him the direction he said he desperately wants in his life.

As the oldest of four children living with a single mother, he said much of his focus has been on helping to raise his youngest brother and sister and acting as a role model in their young lives.

"Getting kicked out of high school, dropping out, it sets a bad example for little siblings," he said, adding he's worried about the road it could lead his siblings down. "They start thinking it's good, since I did it they could do it too.

"I didn't want to set that example so I have to get my GED [certificate] or high school diploma. I have to set a good example for them. I have to be the role model."

The weight of carrying that around poured out as he said goodbye to those he loved most, with tears coming like a waterfall, he said.

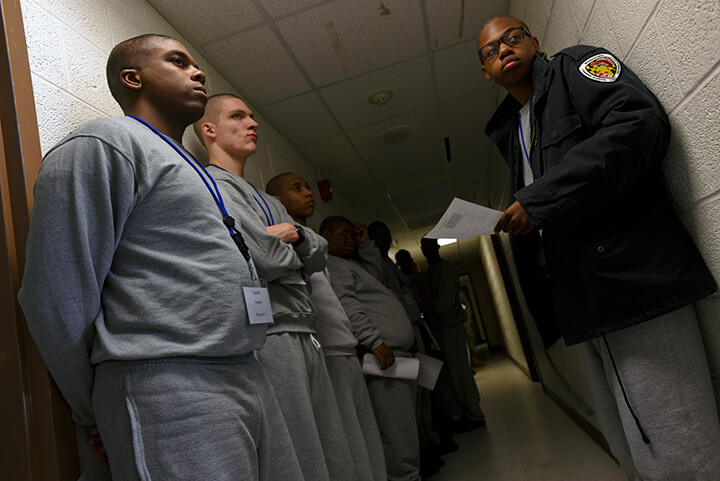

Candidates wait in a hallway in the academy building to be issued their first uniform item, an academy coat. For many candidates, the uniform is an important first step of their journey at the academy and represents the start of big changes to come.

Candidates wait in a hallway in the academy building to be issued their first uniform item, an academy coat. For many candidates, the uniform is an important first step of their journey at the academy and represents the start of big changes to come."I'm a momma's boy and I'm really attached to my sister, my little brothers," Ronny said. "I couldn't stay away from them. They're like my, everything. So to be away from them for [almost] six months, it's hard on me. But I can't give up."

A determined spirit is what keeps his sights on graduation day.

"I committed myself to this and told myself that once I stepped off the bus and was facing the [academy] that I'm going to get through this — there's no backing out, no second chances," he said determinedly.

The same underlying drive to succeed is what also motivates Laneesha Johnson, who said public schools were not for her either.

"Nothing was structured," she said, "and I actually think that I need something to structure me, [or] guide me the right way, and public school was not doing that."

Laneesha, 17, has aspirations of becoming a culinary artist in the Navy and sees Freestate as the path to reaching her goal.

"When I left high school, my administrator … told me this would get me ready for the Navy," she said, referring to the military-style environment of the program. "The physical training is going to help me get myself together and waking up early is going to get me into [a] routine for the Navy."

Earning her high school diploma is the first step before her dreams can become a reality, said Laneesha, adding she feels good about coming to the academy.

"I knew what I was getting myself into," she said of the first day and having to say goodbye to her mom. "I figured it's the best thing for me. I'm going to get myself together, do the right thing and she'll be proud of me at the end. I'm on the right track."

The buzz of clippers fills the room as candidates get the same short haircut, one of the first orders of business after arriving at the academy. Some candidates respond to the haircut with nervous laughter, while other candidates joke and tease each other about their new looks.

The buzz of clippers fills the room as candidates get the same short haircut, one of the first orders of business after arriving at the academy. Some candidates respond to the haircut with nervous laughter, while other candidates joke and tease each other about their new looks.'Let's help these kids'

For Rose, the program director at Freestate, a little more than three years has passed since he found what he describes as his dream job with the academy. A retired Air Force master sergeant, he has worked with children for more than 30 years as a mentor, teacher or coach.

"If I can help a child … realize and achieve success, especially in life in general, then that is something that I'm about," Rose said, adding the ChalleNGe program cried out to him "let's help these kids."

"We need to be able to provide them that opportunity," he said. "In 20 years they could be our legislators, our congressmen, our senators or our president — you never know."

For Rose, the best part of Freestate is watching the teens grow from candidates to cadets, graduates and beyond.

"Once they get the first three or four weeks behind them, they are able to start making that change," Rose said.

Facilitating that change are the cadre members, many of whom are current or former members of the Guard, while others may have served in other military branches. They ensure the discipline, structure and order of the program is maintained and hold cadets accountable for their actions. They are also who the cadets will see and interact with most often during their time in residence at the academy.

That change continues as cadets go through classes preparing them to earn their GED certificate or to return to high school to earn their diploma, said Rose. They also learn life skills, such as how to prepare for a job interview, find a place to live or prepare a personal budget.

From there, they move on to job shadowing, which is when many realize how successful they can be and the light truly goes on, said Rose. That prepares them to work with the staff and a mentor of their choosing on a post-residential action plan.

Ricardo Ballenger balances moving quickly with keeping hold of his bags as he steps off a bus outside the Freestate Academy building. Cadre members stand nearby, ready to provide additional "encouragement" should Ballenger or other cadets lag behind or move too slow.

Ricardo Ballenger balances moving quickly with keeping hold of his bags as he steps off a bus outside the Freestate Academy building. Cadre members stand nearby, ready to provide additional "encouragement" should Ballenger or other cadets lag behind or move too slow."The cadets lay the foundation, establish goals and they determine some of the things they want to do in their lives," Rose said. "You see them start to accomplish some of those goals and expand on them even more, not only in residence, but also in post-residence where they continue on."

The largest hurdle in the growth process for many teens at the academy is simply changing their attitudes, said Rose.

"The biggest problem we have is getting them to understand what they need to do to be successful, especially during the two-week acclimation phase," he said. "Until they get that, it's going to be hard for them."

Some cadets may not see college as an option, said Rose, but the need for an education or job training still exists for them to be successful once they return home.

For this class, all of that is still to come.

Back at the in-processing center, candidates filed out with their bags and were packed tightly into busses that brought them over to the academy building. As they stepped off those busses they saw, for the first time, what would be their home for the next 22 weeks.

One by one, they shuffled uneasily down the sidewalk and through the door. It was one of many doors they would have to choose to walk through — again and again — over the next several months, with only themselves to ask, "Are you ready to come through this door?"